The humming silence of a well-designed circuit can feel like a secret language, whispered only among engineers and seasoned technicians. Yet, for anyone who wants to understand how the electronic world ticks—from a simple LED blinker to the complex motherboard of a computer—learning to read and interpret circuit diagrams is not just a skill; it's a superpower. These schematics are the universal blueprints of electrical systems, unlocking the logic and flow of power that drives our modern lives.

Mastering Reading & Interpreting Circuit Diagrams empowers you to troubleshoot, modify, and even design your own electronic marvels. Forget deciphering cryptic text; schematics offer a visual narrative of electrical relationships, a story told through standardized symbols and lines.

At a Glance: What You'll Learn

- What a Circuit Diagram Is (and Isn't): Understand the difference between a conceptual electrical map and a physical layout.

- The Universal Language: How standardized symbols allow global communication in electronics.

- Key Conventions: Learn the unspoken rules of signal flow, power, connections, and labeling.

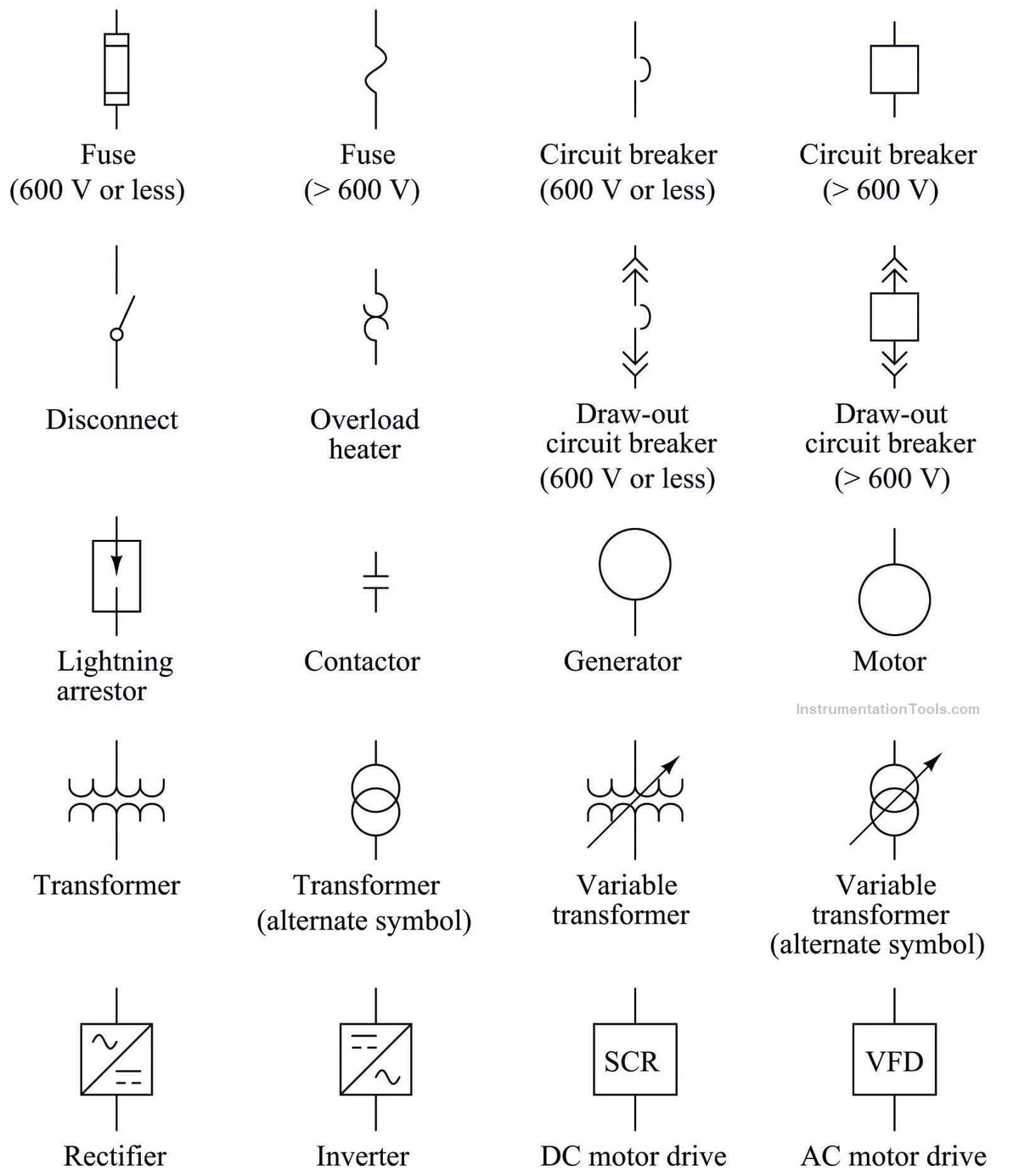

- Decoding Symbols: Familiarize yourself with common component representations, from resistors to integrated circuits.

- Understanding Topology: Grasp how components are arranged in series, parallel, and functional blocks.

- A Systematic Approach: Follow a step-by-step method to confidently analyze any schematic.

- Common Pitfalls: Identify and avoid typical mistakes made by beginners.

- Beyond the Basics: Touch upon advanced concepts for complex designs.

- Developing Fluency: Practical tips to build your expertise and confidence.

The Blueprint of Power: What Are Circuit Diagrams?

Imagine trying to build a complex machine without instructions or a visual guide. Frustrating, right? In the world of electronics, a circuit diagram, often called a schematic, serves as precisely that indispensable guide. It's a visual, standardized representation of an electrical circuit, illustrating precisely how components are interconnected and the intended path of electricity. Think of it as a conceptual map of electrical relationships, detailing functionality rather than physical appearance.

This standardization is a cornerstone of modern electronics. Regardless of their native tongue, an engineer in Tokyo can pick up a schematic designed by a team in Texas and immediately grasp its functionality. It's a truly universal language, fostering collaboration, facilitating troubleshooting, and enabling innovation across borders. Without this common language, sharing designs or diagnosing faults would be an exponentially more complex, if not impossible, endeavor.

What Schematics Convey (and What They Intentionally Omit)

Schematics are powerful because they focus solely on the electrical function and connectivity, cutting through the noise of physical implementation details.

Information a Circuit Diagram Conveys:

- Every Electrical Connection: Lines clearly show where current flows and components meet.

- Component Types: Standardized symbols instantly tell you if you're looking at a resistor, capacitor, transistor, or an integrated circuit.

- Component Values/Part Numbers: Crucial data like "100Ω" for a resistor or "1µF" for a capacitor, often accompanied by specific manufacturer part numbers (e.g., "2N3904" for a transistor), defining their behavior.

- Power Supply & Ground Connections: Where the juice comes from and where it ultimately returns, establishing the voltage references.

- Voltage Levels: Often indicated for different parts of the circuit, guiding analysis and troubleshooting.

- Signal Flow Direction: Arrows and logical arrangement help illustrate how a signal propagates through the circuit.

- Switch Positions: Showing the normal state (open or closed) of various switches.

- Transistor Types & IC Pin Numbers: Specifics vital for understanding the function and correct connection of active components.

Information a Circuit Diagram Intentionally Omits: - Physical Size & Exact Placement: A resistor might be shown next to a capacitor, but in reality, they could be on opposite sides of a circuit board.

- Wire Routing & Lengths: Schematics don't dictate how wires bend or their exact physical paths, nor their lengths.

- Wire Colors: While helpful in physical wiring, colors are irrelevant to electrical connectivity on a schematic.

- Mechanical Mounting: How components are physically attached or enclosed isn't part of the electrical diagram.

- Thermal Considerations: Details about heat sinks or ventilation are handled in other design documents.

- EMI Shielding: Measures taken to prevent electromagnetic interference are also outside the scope of a schematic.

These omitted details are crucial for building a physical circuit, but they are relegated to other documentation like PCB (Printed Circuit Board) layouts, wiring diagrams, or mechanical drawings. The schematic's job is to keep things clean, clear, and focused on electrical truth.

Decoding the Language: Core Conventions You Need to Know

Just like learning any new language, understanding circuit diagrams begins with internalizing a few fundamental conventions. These aren't always explicitly stated on the diagram but are universally understood within the electronics community.

1. Signal and Power Flow: The Invisible Current

- Signal Flow: Most schematics are designed to be read like a book, with the main signal path progressing from left to right. Inputs typically reside on the left, and outputs on the right. This isn't a hard-and-fast rule (sometimes feedback loops will break this), but it's a strong guideline.

- Power Flow: Generally, power connections appear at the top of the diagram (e.g., +VCC, +12V), while ground connections are typically at the bottom (0V reference). This creates a logical flow from power source, through components, and back to ground.

2. Connections vs. Crossings: The Dot Rule

This is one of the most common points of confusion for beginners, but it's surprisingly simple:

- An electrical connection between crossing lines is always indicated by a solid dot at their intersection.

- Lines crossing without a dot do not connect electrically. They are merely passing over or under each other on the conceptual plane.

Imagine wires running over each other without touching; that's the "no dot" scenario. When they're soldered together, that's the "dot" scenario.

3. Reference Designators: Naming the Players

Each individual component in a circuit diagram receives a unique alphanumeric identifier called a reference designator. This allows you to refer to a specific part without ambiguity. Common designators include:

- R for Resistor (e.g., R1, R22)

- C for Capacitor (e.g., C5, C101)

- L for Inductor (e.g., L3)

- D for Diode (e.g., D1, D4)

- Q for Transistor (e.g., Q7, Q9)

- U or IC for Integrated Circuit (e.g., U1, IC2)

- SW or S for Switch (e.g., S1)

- J for Jack/Connector (e.g., J1)

- LED for Light Emitting Diode (e.g., LED1)

- F for Fuse (e.g., F1)

These designators are critical for troubleshooting, ordering parts, and discussing specific elements of the circuit.

4. Component Values & Part Numbers: The Details that Matter

Adjacent to each component symbol, you'll find its specific electrical value or part number:

- Resistors: Values in Ohms (Ω), kilohms (kΩ), or megohms (MΩ). (e.g., 100Ω, 4.7k, 1M).

- Capacitors: Values in Farads (F), microfarads (µF), nanofarads (nF), or picofarads (pF). (e.g., 1µF, 22nF, 100pF).

- Inductors: Values in Henrys (H), millihenrys (mH), or microhenrys (µH).

- Integrated Circuits & Transistors: Often represented by their manufacturer part numbers (e.g., "555 Timer", "LM324", "2N2222").

These values dictate the component's role in the circuit and are non-negotiable for proper functionality.

5. Implicit Connections: Ground and Power

To prevent schematics from becoming an impossible tangle of lines, engineers use a clever shorthand: implicit connections.

- Ground Symbols: All ground symbols (representing the zero-volt reference point) throughout the diagram are implicitly connected. You won't see lines running from every ground symbol back to a central point; it's understood they're all electrically common.

- Power Supply Symbols: Similarly, power supply symbols (e.g., +5V, +12V, VCC) with the same label are also implicitly connected. If you see "+5V" at the top left and again in the middle of the diagram, those points are electrically identical.

This convention dramatically reduces visual clutter, making complex schematics far more readable.

The Alphabet of Electronics: Common Component Symbols Explained

To truly read a schematic, you need to recognize the "alphabet"—the standardized symbols that represent different electronic components. Here are some of the most common:

Resistors: The Current Controllers

Resistors restrict the flow of current, dissipating energy as heat. Their value is measured in Ohms (Ω).

- Fixed Resistor (US Symbol): A zigzag line.

- Fixed Resistor (European Symbol): A simple rectangle. You'll encounter both depending on the schematic's origin.

- Variable Resistor (Potentiometer/Rheostat): Adds an arrow through or over the fixed resistor symbol, indicating adjustability.

Capacitors: The Charge Storers

Capacitors store electrical charge and block DC current while allowing AC to pass. Their value is measured in Farads (F).

- Non-Polarized Capacitor: Two parallel lines of equal length. These can be connected in any orientation.

- Polarized Capacitor (Electrolytic): One straight line and one curved line. The straight line represents the positive terminal, and the curved line (or sometimes a thicker bar) represents the negative terminal. Polarity is critical; connecting these backward can cause damage or explosion.

- Variable Capacitor: Adds an arrow through the capacitor symbol, allowing its capacitance to be adjusted.

Inductors: The Magnetic Field Makers

Inductors store energy in a magnetic field when current flows through them. Their value is measured in Henrys (H).

- Air-Core Inductor: A series of curved loops.

- Iron-Core Inductor: The series of loops with two parallel lines drawn through the center, indicating a magnetic core for increased inductance.

Diodes: The One-Way Gates

Diodes allow current to flow in only one direction (from anode to cathode).

- Diode: A triangle pointing towards a line. The triangle's base is the anode (positive input), and the line is the cathode (negative output).

- Light Emitting Diode (LED): The standard diode symbol with two small arrows pointing away from it, indicating light emission.

- Zener Diode: Similar to a diode but with "wings" on the cathode line, designed to maintain a stable voltage in reverse breakdown.

Transistors: The Amplifiers and Switches

Transistors are semiconductor devices used for amplifying or switching electronic signals and electrical power. The most common types are Bipolar Junction Transistors (BJTs).

- BJT (NPN Type): A vertical line (base) with two angled lines (collector and emitter). An arrow on the emitter line points outward, indicating NPN.

- BJT (PNP Type): Similar to NPN, but the arrow on the emitter line points inward, indicating PNP.

- MOSFET (N-Channel / P-Channel): More complex symbols, typically showing a gate, drain, and source, often with a subtle break in the channel line and an arrow.

Integrated Circuits (ICs): The Brains of the Operation

ICs are miniature electronic circuits fabricated on a single piece of semiconductor material. They range from simple logic gates to complex microprocessors.

- General IC (Rectangle): Often represented as a plain rectangle, labeled with its part number (e.g., 555, LM741, ATmega328P). Pin numbers are usually around the perimeter.

- Operational Amplifier (Op-Amp): A triangle with two inputs (inverting and non-inverting) and one output, plus power connections. Op-amps are fundamental building blocks for many analog circuits.

Switches: The Connectors and Disconnectors

Switches mechanically complete or break an electrical connection.

- Single Pole, Single Throw (SPST): A simple lever that opens or closes one circuit.

- Single Pole, Double Throw (SPDT): A lever that connects one common terminal to one of two other terminals.

- Double Pole, Double Throw (DPDT): Essentially two SPDT switches operated by a single mechanism, used for switching two separate circuits simultaneously.

Sources & Batteries: The Power Providers

These symbols represent where the energy comes from.

- DC Voltage Source: A circle with plus (+) and minus (-) signs.

- AC Voltage Source: A circle with a sine wave symbol inside.

- Battery: Alternating long (positive) and short (negative) parallel lines. Multiple cells are shown by repeating the pattern.

Understanding these symbols is like learning the alphabet; once you know them, you can start to form words and sentences, which in circuit diagrams, translates to understanding how components work together.

Building Blocks of Brilliance: Understanding Circuit Topology

Knowing the individual components is just the start. The real insight comes from understanding how they are arranged—their topology—which dictates their collective behavior.

Series Connections: The Shared Current Path

When components are connected end-to-end, forming a single path for current, they are in series.

- Characteristics: All components in a series share the same current. The total voltage across them divides among the components, and the total resistance (or impedance) is the sum of individual resistances.

- Analogy: Imagine a single lane road with multiple toll booths. Every car must pass through every toll booth.

Parallel Connections: The Shared Voltage Path

When components are connected across the same two points in a circuit, they are in parallel. This means they effectively share the same voltage.

- Characteristics: All components in parallel experience the same voltage across them. The total current flowing into the parallel combination divides among the branches, and the total resistance is less than the smallest individual resistance (current has more paths to flow).

- Analogy: Think of a multi-lane highway with multiple gas stations, each accessible from the same stretch of highway. Each car sees the same "highway" voltage, but can choose which "station" (component) to flow through.

Combined Circuits: The Real World

Most practical circuits are a blend of series and parallel elements. The key to analyzing them is to break down the circuit into smaller, manageable sections of purely series or parallel components. For example, a common approach is to simplify parallel resistors into an equivalent single resistor, then combine that in series with other components.

Functional Blocks: Recognizing Common Patterns

Experienced schematic readers don't just see individual components; they recognize common arrangements that perform specific functions. These are called functional blocks:

- Voltage Dividers: A series of two resistors used to "tap off" a lower voltage from a higher one.

- Filters: Combinations of resistors, capacitors, and inductors used to pass or block certain frequencies (e.g., low-pass, high-pass filters).

- Amplifiers: Circuits (often centered around transistors or op-amps) designed to increase the power or amplitude of a signal.

- Current Sources: Circuits that provide a constant current regardless of the load.

Being able to spot these functional blocks allows you to quickly grasp the purpose of a section of the circuit without needing to analyze every single component in detail. It’s like instantly knowing a certain arrangement of words forms a common idiom or phrase.

Your Blueprint for Success: A Systematic Approach to Reading Schematics

Approaching a new schematic can feel overwhelming, especially if it's complex. But with a systematic method, you can break down even the most daunting diagrams into understandable parts.

1. Establish Your Bearings: Start with the Obvious

Don't dive into the minutiae immediately. Begin by getting the lay of the land:

- Inputs and Outputs: Locate where signals enter and leave the circuit (e.g., connectors, sensor inputs, speaker outputs).

- Power and Ground: Identify the power supply connections (e.g., +5V, +12V, VCC) and all ground symbols. This establishes the voltage rails that power everything.

- Major Sections: Look for any clear divisions or labeled functional blocks (e.g., "Power Supply," "Audio Amplifier," "Microcontroller").

2. Trace the Signal Paths: Follow the Flow

Once you have your bearings, start tracing the primary signal paths from input to output, or from power through critical components.

- Identify Stages: As you trace, try to determine what each section of the circuit does. Does it amplify the signal? Filter it? Convert it? Compare it?

- Annotate (Optional but Recommended): For complex diagrams, print it out and use a highlighter or pen to mark the signal path, voltage levels, or functional blocks.

3. Identify Critical Components: Where the Action Happens

Focus your attention on the active components and feedback paths, as these largely define the circuit's behavior and purpose.

- Active Components: Transistors, Integrated Circuits (ICs), Op-Amps, microcontrollers. These are the "brains" or "muscle" of the circuit, actively manipulating signals.

- Feedback Paths: Look for connections from the output of a stage back to its input. Feedback is crucial for stability, gain control, and creating specific responses (e.g., oscillators).

- Component Values: Double-check the values of resistors, capacitors, and inductors around these active components; they often set the operating points, frequencies, or gain.

4. Utilize Supplementary Information: The Unwritten Context

A schematic rarely stands alone. Always look for additional documentation that provides crucial context.

- Title Blocks: These often contain the diagram's title, revision number, author, date, and sometimes a brief description of the circuit's function.

- Notes: Schematics often include specific notes about operating conditions, special instructions, or component ratings. Don't skip them!

- Part Tables/Bill of Materials (BOM): These list all components, their reference designators, values, and often manufacturer part numbers. For unfamiliar components (e.g., a specific IC part number like "2N3904"), looking up the datasheet is essential to understand its pins, operating characteristics, and function. Learn more about circuit diagrams and their associated documentation to get the full picture.

5. Simulate Circuits: Observe and Learn

For serious analysis and deeper understanding, especially if you're experimenting or troubleshooting, consider using circuit simulation software.

- Tools: Programs like LTspice (free), Proteus, or Multisim allow you to build the circuit virtually from the schematic.

- Benefits: You can apply inputs, measure voltages and currents at any point, observe waveforms, and test "what if" scenarios without ever touching a soldering iron. This interactive approach can drastically deepen your understanding of how the circuit actually behaves.

Navigating the Minefield: Common Beginner Mistakes to Avoid

Even seasoned professionals made these mistakes early on. Being aware of them will save you frustration and potential damage.

- Assuming Physical Layout: This is the cardinal sin. Remember, schematics are conceptual maps of electrical connections, not blueprints for physical arrangement. A beautifully laid out schematic might translate to a physically messy board, and vice-versa.

- Confusion with Crossing Lines: The "dot rule" is critical. No dot means no connection, period. Many early troubleshooting hours are wasted tracing paths that aren't actually connected.

- Ignoring Implicit Connections: Forgetting that all ground symbols are connected and all identically labeled power symbols (e.g., all "+5V" points) are also connected can lead to wildly incorrect assumptions about circuit paths and voltages.

- Overlooking Component Values/Ratings: A resistor's value (e.g., 100Ω) determines its behavior, but its power rating (e.g., 1/4W, 1W) determines its operational integrity. Ignoring ratings can lead to components burning out. Similarly, capacitor voltage ratings are vital.

- Trusting Schematics Blindly: While generally reliable, schematics can contain errors, particularly in early design stages or user-contributed diagrams online. Always compare the schematic to the physical circuit if possible, especially when troubleshooting. Actual implementations can sometimes deviate.

Beyond the Basics: Advanced Concepts for the Curious Mind

As you gain fluency, you'll encounter more sophisticated schematic conventions designed for highly complex systems.

- Hierarchical Design: For massive circuits (like microprocessors), a single flat schematic would be impossible to read. Engineers use hierarchical designs, where a top-level schematic shows high-level functional blocks, and each block then has its own sub-schematic detailing its internal components.

- Bus Notation: When many parallel conductors carry related signals (e.g., 8 data lines in a computer), drawing each line individually would be unwieldy. Bus notation uses a single thick line with a slash and a number (e.g., "/8") to represent multiple conductors. Individual lines can then "break out" from the bus.

- Test Points (TP): These are specific locations on a circuit designated for taking measurements during testing or troubleshooting. They're often marked with a circle or cross symbol labeled "TP1," "TP2," etc.

- Net Names/Numbers: In multi-page schematics, a "net" (an electrically connected set of points) might span across several pages. Net names (e.g., "DATA_BUS_0", "CLK_IN", "ADC_OUT") are labels attached to these lines, indicating that all points with the same net name are electrically connected, regardless of their physical separation on the diagram.

Mastering the Art: Developing Fluency and Confidence

Like learning to play a musical instrument, mastery of schematic reading comes with consistent, deliberate practice. It's not about memorizing every possible symbol, but about developing a systematic approach and an intuitive understanding.

- Practice, Practice, Practice: Start with simple circuits (e.g., an LED blinker, a basic power supply) and progress to more complex ones. Try redrawing schematics by hand; this forces you to actively process the connections rather than just passively observing.

- Active Analysis: Ask "Why?": Don't just identify components; question their purpose. "Why is this resistor here? What does this capacitor do in this position? How would changing this value affect the circuit?" Perform simple calculations (Ohm's Law, voltage division) to verify expected behavior. Compare different designs for similar functions to understand trade-offs.

- Diverse Sources: Expose yourself to a wide variety of schematics. Look at diagrams from textbooks, electronics kits, open-source projects (like Arduino shields), and service manuals for consumer electronics. Each source might have slightly different drafting styles, but the core conventions remain.

- Cultivate Meta-Skills: Learn how to research unfamiliar elements effectively (datasheets are your best friend). Develop the ability to infer meaning from context and to systematically analyze an unknown circuit step-by-step, even when you don't recognize every single component.

Developing fluency in reading and interpreting circuit diagrams is a journey, not a destination. Each schematic you tackle builds your mental library of patterns and conventions. With consistent effort, you'll soon find yourself effortlessly navigating the intricate electrical landscapes that power our world, turning the secret language of electronics into a clear, understandable narrative.